At last, a fair and accurate book on the life and politics of Jinnah

Empowering Weak & OppressedNisar Ali Shah

Safar 21, 1419 1998-06-16

Book Review

by Nisar Ali Shah (Book Review, Crescent International Vol. 27, No. 8, Safar, 1419)

QUAID-I-AZAM MOHAMMAD ALI JINNAH - HIS PERSONALITY AND HIS POLITICS by S M Burke and Salim Al-Din Quraishi. Oxford University Press, Karachi, Pakistan. 1997. pp: 412.

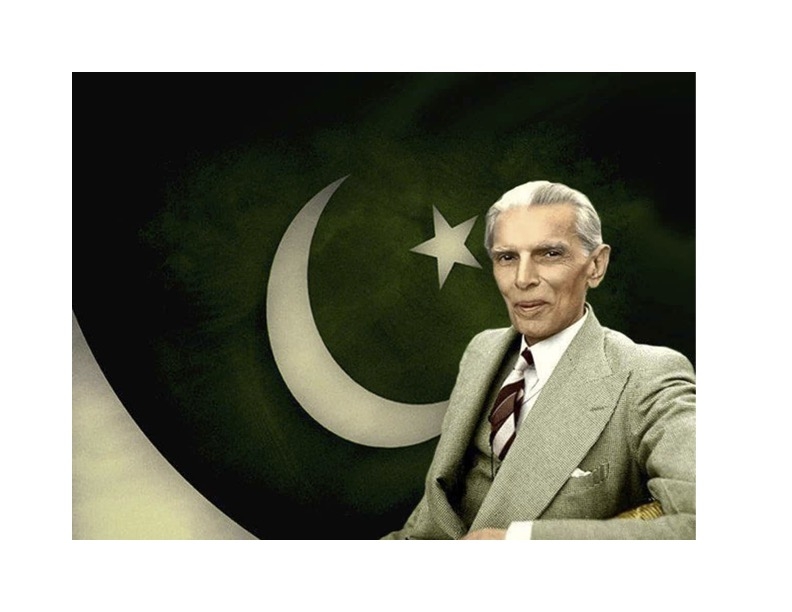

Whenever India’s independence from Britain is mentioned, two names connected with the event dominate: ‘Mahatma’ Karamchand Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Meanwhile, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, is either mentioned only in passing, usually as villain of the piece, or totally ignored.

Such is the prejudice Jinnah experienced from both British and Hindu politicians in his life. This prejudice existed before, during and after the independence of India. Jinnah was undermined by Hindu politicians to their own loss because the pretence not to understand him led to the partition of the subcontinent. The ultimate result was that the country was carved out in such a haphazard manner that its consequences still linger on.

This new book, part of the Oxford University Press’s Jubilee Series, analyses how the State of Pakistan was created and reappraises the personality and politics of the State’s founder, ‘Quaid-i-Azam’ (the great leader) Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

Perhaps the first point to make is that, for a change, both authors are sympathetic and knowledgeable on Pakistani affairs. Professor S M Burke is a former professor and consultant in South Asian Studies at the University of Minnesota. His co-author in this venture is another scholar, Mr Salim Al-Din Quraishi, Head of the Modern South Asian Section of the British library.

Among the history makers of this century Mohammad Ali Jinnah is perhaps the most misunderstood. The reasons for this are twofold. First, the history of Indian independence, partition, and Pakistan has been dominated by Hindu historians, who have inherited the kind of animosity against Muslims usually reserved for their most bitter enemies.

Second, the British historians, who wrote about Jinnah, Pakistan and Muslims, went one better. The British did not write much about him because he stood up to them, because of Jinnah’s upright, transparent personality, correct manners, and above all, the way in which he presented his irrefutable arguments. Lord Mountbatten, Britain’s last viceroy in India, found him more than his match.

Had Jinnah behaved against his conscience, as half-naked, intentionally homeless, starving in public, travelling third class rather than in first as he always did, his value and status in British eyes would have been enhanced. But Jinnah was his own man. He never felt compelled to resort to such a ridiculous position and reduce himself to degrading theatrical acts, as others did. He did not lead a double life. Jinnah’s greatness lies in the fact that at all times he presented himself as he really was, irrespective of how others wanted him to behave.

Meanwhile Pakistanis also have not written well about either Jinnah or Pakistan to redress the imbalance. So, the gap was filled by outsiders and foreigners with little sympathy for these subjects. The result is that Pakistan and Jinnah are universally misunderstood, even by Muslims particularly in the Arab world. His critics’ dislike of him also emanates from a misunderstanding that he wanted to divide India to satisfy his own ego.

Jinnah denied this time and again. He was determined, though, to fight for the civil and political rights of the Muslims within the union of India. His concentration on this point was unbreakable. His long membership of and active participation in the Indian National Congress Party testify to this.

During his dealings with the Congress, he thought of himself as an Indian nationalist and a believer in Hindu-Muslim unity. After working within the Congress Party for many years he became disillusioned with the machinations of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and disgusted with Nehru and other Hindu leaders’ prejudices. The Hindus at no time showed any magnanimity towards their Muslim fellow citizens which made it difficult for Jinnah to maintain his faith in the possibility of a permanent amicable relationship between India’s two major peoples.

Jinnah’s relations with the Congress lasted only long enough for him to discover its true nature, which he found incompatible with the aspirations of the Muslims who longed for their civil and political rights to be protected under constitutional and electoral guarantees. Disillusioned and disappointed, Jinnah finally realised that the parting of ways was unavoidable and made a clean break from the party.

These are some of the historical points elaborated in this book which give the reader a greater insight into what really happened and what could have been averted.

Gandhi himself admitted that religion was the inspiration of his politics long before Jinnah started to demand a separate homeland for Muslims. Gandhi frankly declared in his autobiography (1927): ‘I can say without the slightest hesitation, and yet in all humility, that those who say that religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means.’

In another book, Gandhi is quoted as saying: ‘If I seem to take part in politics, it is only because politics today encircles us like the coils of a snake from which one cannot get out no matter how one tries. I wish to wrestle with the snake. I am trying to introduce religion into politics.’

Nehru, too, concedes that Gandhi introduced religion into politics. He says in his autobiography, ‘Gandhiji, indeed, was continuously laying stress on the religious and spiritual side of the movement. His religion was not dogmatic, but it did mean a definitely religious outlook on life, and the whole movement was strongly influenced by this and took a revivalist character so far as the masses were concerned.’

Jinnah, on the other hand, was convinced that Hindu-Muslim co-operation was a noble and achievable aim provided the political and religious rights of the Muslims could be safeguarded. A united India, free from tensions and social chaos was Jinnah’s original dream. But an ideologically united, politically integrated, constitutionally secure India could not be achieved because Gandhi and Nehru never reassured the Muslims that they would be safe in a Hindu-dominated country. The final chance for this was in 1945 when the Cabinet Mission Plan was accepted by Jinnah but rejected out of hand by Nehru.

If Gandhi and Nehru had had their way, the Muslims would have suffered permanent Hindu majority domination in the name of democracy. A Pakistan, albeit truncated, mutilated or moth-eaten, was the only option Jinnah could accept. The book is so persuasively written and painstakingly researched that it is difficult to argue with its convincing evidence that Gandhi left no option for Jinnah but to demand a separate State for Muslims.

It is most unfair that Jinnah is often described by Indian and British writers as arrogant and unfriendly. The authors of this book have diligently researched Jinnah’s past to discover the sort of person he really was. Their findings after meticulous appraisal belie this description. Even the television footage, shown in Britain on his birth anniversary on December 25 last year, does not support that idea of Jinnah. On the contrary, he is shown smiling at Gandhi, receiving him respectfully at his Bombay residence with good grace. His character assassination may be based on the belief that if enough mud is thrown at him, some is bound to stick.

Had Jinnah been dealing with such Hindu leaders as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who understood the tears of the Muslims and an accord at the Lucknow Pact of 1916 between the Congress and the Muslim League, or Gopal Krishna Gokhale, another realist who got on well with Jinnah and understood Hindu-Muslim aspirations well, India would be one country today, and a more powerful and prosperous one perhaps.

It was after Gokhale’s death in 1915, and Tilak’s in 1920, that the political atmosphere changed radically. Had either or both lived a bit longer, and Jinnah at the helm of Muslim affairs, not only might India have remained undivided but independence may also have come sooner. The two communities would have had a shared priority: to win freedom for their country. There would have been a will to succeed and a meeting of minds among the leaders of all factions. Instead, the situation rapidly deteriorated into virtual warfare.

Although Gandhi comes in for a great deal of criticism, the authors make it plain at the outset that their ‘purpose in discussing the extraordinary aspects of Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy and political tactics is not to question his saintliness nor to deny his status as the most venerated Hindu of modern times. But this book is not on the lofty subjects of religion and ethics. It is on the down-to-earth subject of politics and we needed to explain our view that Gandhi was not a practical politician and that he, and not Jinnah, was really responsible for wrecking the chances of Hindu-Muslim unity.’

A lot of attention is focused on Gandhi’s theory of non-violence by writers and journalists throughout the world. Jinnah’s tactics were essentially non-violent too, but nothing is written about this. In fact, one of the greatest violent acts in the history of mankind was committed in India when an approximately two million civilians were murdered under the very noses of Nehru and Gandhi. The authors have undertaken the herculian task of explaining the duplicitous character of Gandhi’s political thought, particularly when Jinnah was made to look like a separatist and communal leader while Gandhi cultivated a non-violent, non-sectarian facade. This sham was also promoted, of course, by the Hindu media barons who dominated India’s press.

The authors have quoted from some Hindu writers and politicians who did not approve of Gandhi’s politics either. For instance, Tilak is quoted as saying, ‘I have great respect and admiration for Gandhiji, but I do not like his politics. If he would retire to the Himalayas and give up politics, I would send him fresh flowers from Bombay every day because of my respect for him.’

On May 9, 1933, a joint statement by Subhas Chandra Bose and Villabhai Patel declared: ‘We are clearly of the opinion that as a political leader Mahatma Gandhi has failed. The time has, therefore, come for a radical reorganisation of the Congress on a new principle and with a new method. For bringing about this reorganisation a change of leadership is necessary.’

Throughout this book, the writers’ experience, knowledge and incisive analysis of the events before, during and after the creation of Pakistan are convincingly explained. There is no confusion or ambiguity as to what they mean. No events of that period are lost in the mist of time or blurred by subsequent developments. The praise it has received is well earned. It is a serious book and can be read by people with all shades of opinion.

It is essential reading for historians, teachers and journalists. Having read it, the reader will come to the same conclusion as the authors have reached: that Gandhi was not a practical politician, that he, and not Jinnah, who shattered the unity of India.