The Israel-Azerbaijan-Turkiye Tripartite Alliance Against Iran

Developing Just LeadershipOmar Ahmed

Rabi' al-Awwal 08, 1447 2025-09-01

News & Analysis

by Omar Ahmed (News & Analysis, Crescent International Vol. 55, No. 7, Rabi' al-Awwal, 1447)

Iran and the Axis of Resistance stand virtually alone in West Asia. The Islamic Republic’s revolutionary ideology, forged in opposition to regional monarchies and the zionist entity, has nonetheless endured and mounted a credible challenge to entrenched powers.

While hostility from Persian Gulf monarchies is expected, a less scrutinised front has emerged to Iran’s north and northwest. Turkiye and Azerbaijan, two Turkic neighbours with deepening ties to Tel Aviv, are key players in a growing axis that aims to isolate and weaken Tehran’s regional reach.

It is a harsh reality, often obscured by headline rhetoric. Yet the alignment of Baku, Ankara, and Tel Aviv is not a matter of speculation, it is an entrenched strategic posture.

Hydrocarbons and hegemony

The partnership between Azerbaijan and the occupation state extends well beyond energy trade. Baku supplies over 60 percent of the zionist entity’s oil needs, a relationship formalised through multi-billion dollar investments like Azerbaijan’s $1.25bn stake in Tamar gas field.

For Tel Aviv, this ensures a reliable, non-Arab energy source that circumvents dependency on regional rivals. In fact, the largest share of the entity’s oil comes from Azerbaijan, whose yearly shipments total over $1.4 billion. For Azerbaijan, the partnership grants access to advanced Israeli military technologies that have proven decisive in its wars with Armenia.

Turkiye has reaffirmed its ambition to serve as a regional energy hub, leveraging its position at the crossroads of Eurasia. This facilitates the flow of Azerbaijani oil through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline and natural gas to Europe via the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP).

Azerbaijan’s motivations go deeper than transactional energy deals. Despite its majority-Shia population, Baku’s secular elite have embraced ethno-nationalism over religious affinity. The historical division of Azeri populations between northern Iran and Azerbaijan, a legacy of the Treaty of Turkmenchay feeds Baku’s antagonism toward Tehran.

On January 8, 2025, an Iranian sermon leader publicly denounced the Turkish and Azerbaijani presidents by invoking the 1514 Battle of Chaldiran, where the Ottoman Sultan Selim defeated the Persian Shah Esmail Safavi. He vowed that the heirs of Safavi Iran would one day raise Persian flags over Baku and other cities that once belonged to the Persian Empire.

Yet Iran’s longstanding support for Armenia, particularly during the second Karabakh war, only hardened this divide. Meanwhile, Baku’s assertive national identity and demands for Azeri-language rights inside Iran have fuelled further tension.

Another flashpoint is the proposed Zangezur Corridor, a Turkish and US-backed transport route through southern Armenia that would connect Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave and on to Turkiye, entirely bypassing Iran. Tehran views the project as a direct threat to its access to Armenia and the broader Caucasus, warning it could redraw regional borders at its expense.

Arms, alliances, and antagonisms

The occupation state was quick to back Azerbaijan militarily, recognising its independence in 1991 and soon supplying weapons during the first Karabakh war. By 2020, Tel Aviv accounted for nearly 70 percent of Baku’s military imports, providing drones, missiles, and electronic warfare systems that proved pivotal in Azerbaijan’s battlefield dominance.

The synergy is undeniable: in 2024, a joint defence expo in Baku was co-hosted by the zionist entity’s Aerospace Industries and Turkiye’s Baykar, led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s own son-in-law, Selcuk Bayraktar.

This trilateral coordination is underpinned by a shared opposition to Iranian influence. While Ankara publicly criticises Tel Aviv, its defence industry quietly aligns with Israeli interests, with Turkiye pursuing regional energy corridors that deliberately exclude Iran.

For Iran, which is ideologically opposed to Israel, such things are an anathema. But Azerbaijani rulers remember those who supported the country during times when it was down.

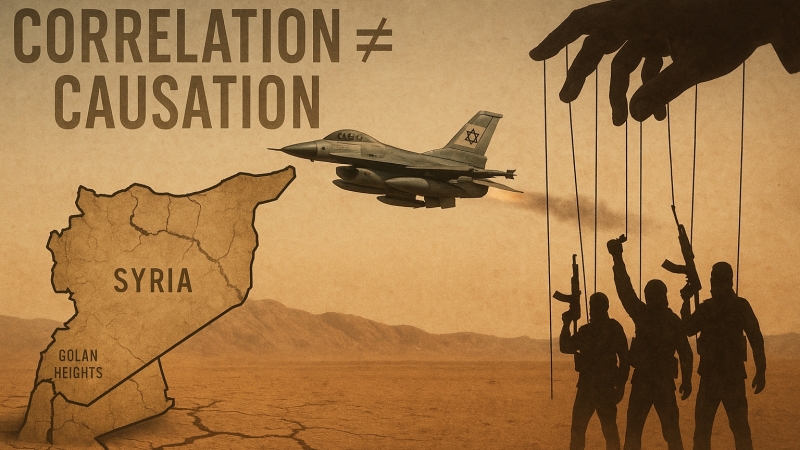

Redrawing the Syrian map

The most striking manifestation of this axis is unfolding in Syria. In July 2025, Turkiye declared its intent to channel Azerbaijani natural gas to Aleppo, marking a bold entry into the energy and political void left by the collapse of the Asad government.

According to Turkish Energy Minister Alparslan Bayraktar, deliveries was set to begin last via Kilis, a province near the Syrian border. The project aims to supply 3.4 million cubic meters of gas per day, generating 900 megawatts of power for Aleppo. Turkiye has also pledged 2 billion cubic meters annually to bolster Syria’s energy infrastructure and invest in renewable energy.

During the 2024 “revolution” that toppled the Asad government, Turkiye-backed Sunni factions flew Turkish flags and operated sophisticated drones. Although Ankara denies direct involvement, its military footprint across northern Syria and influence over factions like the Syrian National Army (SNA) and remarks by US President Donald Trump suggest otherwise.

Former Al-Qaeda commander, Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, since rebranded as President Ahmad al-Sharaa, now at the helm in Damascus is leading an administration that is fundamentally hostile to Hizbullah and, by extension, Tehran. Formerly reliant on Syrian territory to supply Palestinian and Lebanese resistance factions, Iran now finds itself cut off.

Some SNA commanders have since integrated into the new Syrian armed forces under Jolani, further cementing Turkiye’s foothold in the country.

Turkiye's military presence in northern Iraq further curtails Iranian influence, with Ankara launching operations against Kurdish factions under the watch of the pro-Tehran government in Baghdad.

Despite public outrage across the Islamic world over the zionist entity’s war on Gaza, key Muslim-majority states continue to nurture quiet alliances with Tel Aviv, revealing a dissonance between public sentiment and statecraft.

Public theatre, private deals

Despite fiery rhetoric from Turkish officials and media outlets condemning the occupation army’s war crimes in Gaza, the Ankara-Tel Aviv alliance remains intact. Azeri President Ilham Aliyev once likened Baku’s relationship with Israel to an iceberg—"nine-tenths of which is invisible to outsiders.” The same could be said of Turkiye.

Material interests trump populist narratives. For Baku and Ankara, Israeli partnership yields energy security, military superiority, and geopolitical leverage—at Iran’s expense.

For Tehran, the reality is stark: regional actors who wave the Palestinian flag do not necessarily stand with the Resistance Axis. Rhetoric alone cannot conceal a strategic convergence rooted in countering the Islamic Republic.