The Political Thought of Ayatullah Murteza Mutahhari

Author(s): Mahmood T. Davari

Publisher: RoutledgeCurzon

Published on: Dhu al-Qa'dah, 1425 2005-01

ISBN: 0-203-33523-6

No. of Pages: 212

Introduction

by Mahmood T. Davari

(Mahmood T. Davari is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Qum)

The manifestations of Islamism are quite visible, today, not only in the Islamic world, but also in the West among Muslim minorities. Islamic practices, such as wearing the Islamic veil (hijab), growing a beard, consuming Islamically slaughtered (halal) meat, non-alcoholic drinks, etc., are all familiar to Western people. These rituals are currently observed, not only in traditional and ordinary Muslim circles, but also by enthusiastic top Muslim academics and political activists who have been educated in well-known Western universities.

While most Islamic societies were under the influence and severe pressure of (state-) secular ideologies such as Marxism, socialism and nationalism for almost half a century, the tendency towards Islamism rose and gradually expanded in reaction to those state-propagated ideologies. At first, the Islamist movements were relatively limited and local; however, they progressed and intensified, covering the vast majority of people, influencing their lives and ideals, mobilizing them towards independence and self-reliance. Thus an international network was established after the victory of the Islamic Revolution in Iran (1979) that has become a source of hope even for many non-Islamic movements. This revolution undoubtedly played a role in promoting Islamic feelings and consciousness among the Muslim masses around the globe. The Islamists, regardless of their differences in policy, adopted Islam as their identity, their way of living and their strategy. However, they may be classified into three groups: (i) the rigid, extreme, superficial; (ii) the moderate, logical and truthful; and (iii) the liberal, pragmatist and compromising. All three share the view that Islam holds the key to their present and future problems.

This present massive tendency towards Islamism or, in my own words, an Islamic type of living, among Muslims, is indeed the result of several lifetime endeavors by Muslim theoreticians and political activists, including Ayatullah Mutahhari. His role is more visible than others, perhaps, in rendering Islam an up-to-date comprehensive social-political ideology compatible with modern times and present needs. His writings are still widely distributed and massively read in Islamic groups and Shi‘ite communities. As a distinguished Islamic leader, he played a very important role, particularly in the case of Iran’s Islamic Revolution. Therefore, he can be considered as a major force behind present-day Islamism and Islamic movements, especially in its Shi‘i branch.

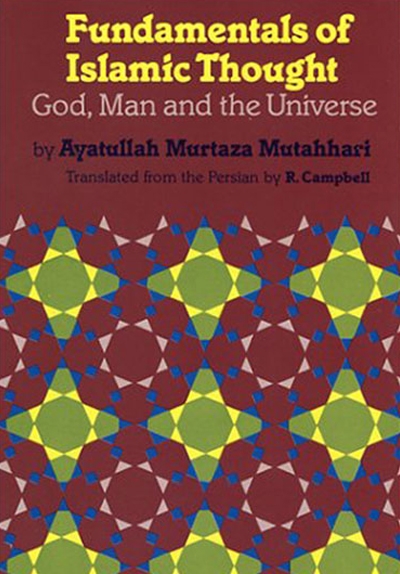

Ayatullah Hajj Shaikh Murtaza Mutahhari Farimani (1920–79) was from a clerical family, a pupil of Ayatullah Khomeini, a university Professor of Philosophy and a Mujtahid (jurist) in Islamic law at the Shi‘ite seminary. He is highly regarded among the most distinguished and respected scholars, not only in the Islamic world, but also by Islamologists in the West. He has been described and praised with words and phrases that are rarely used for others, such as ‘the Son of the Time’,1 ‘one of the most prominent contemporary intellectual figures among the Iranian clergy’,2 ‘a powerful intellectual force for almost a quarter of a century’,3 ‘one of the principal architects of the new Islamic consciousness in Iran’,4 ‘a scholar who best delivered the Islamic ideology from the very depths of the Islamic sacred history, and rendered it a legitimate historical updating of the Muslim doctrinal self-understanding’,5 ‘an outstanding political theorist, reformer and radical activist’,6 ‘a high ranking thinker, philosopher, jurist, and a rare Islamologist’,7 ‘a reformist of Islamic thought in modern times’,8 ‘a guardian of the frontiers of the Islamic ideology’,9 ‘a theoretician of Islamic rule’10 and ‘the ideologue of Islam-i fiqahati [an interpretation of Islam which maintains that only Mujtahids are authorized to interpret the Islamic texts and rule the people]’.11 The then President (and present leader) Khamenei¯ stated that ‘Mutahhari’s views have formed the theoretical foundations of our (Islamic) Republic’.12 Hence, the importance of Mutahhari for understanding modern Islamic social and political philosophies, the Islamic movement and Islamic Iran, is indisputable.

The importance of Mutahhari’s works is based, first, on their comprehensiveness and complexity. Similar to Marxist totalism, they cover almost all parts of human social-political issues, including theology, philosophy, history, sociology, ethics, education, the law, economics and politics. Simultaneously challenging traditionalism, Marxism, secularism and monarchism, Mutahhari presents an alternative total Islamic system, Islamic world view and social political ideology. Second, Mutahhari offers a unique type of analysis. He neither builds his arguments by means of reason (‘aql) alone – as does the liberal – nor does he limit himself to a literal understanding of religious texts – as do conservatives. Supporting his arguments with religious texts, Mutahhari prefers rational interpretations. While referring to the Islamic texts, he does not neglect man’s intellectual achievements.

Although a number of articles and books concerning Mutahhari’s life and views have been published in the West and in Iran after his assassination, nevertheless, owing to the unsatisfactory nature of the sources, no major comprehensive study of his life and socio-political philosophy has yet appeared. In his ‘Introduction’ (1985), Hamid Algar deals only with Mutahhari’s biography, not his works and philosophy.13 Michael J. Fischer and Mehdi Abedi’s Debating Muslims (1990) deals with Mutahhari only as a part of their anthropological studies on dialogues about postmodernity and tradition within Muslim communities.14 Apart from their brief biography of Mutahhari, they restrict themselves to Mutahhari’s Islam va Iran and his views about Iranian nationality. Farhad Nomani and Ali Rahnema’s analysis of Mutahhari’s political thought (1990) is part of their post-Revolution Iranian studies. However, they did not mention the events of Mutahhari’s life. Further, they deal mainly with some less important aspects of his political views and economic philosophy. Mutahhari’s milestone books on economics, Nazari bi Nizam-i Iqtisadi-yi Islam and Mas’alih-yi Riba and also his views on the theory of Vilayat-i Faqih are not discussed in their studies.15 Although J. G. J. Haar’s interesting article on Mutahhari’s life and thought (1990–2) does not leave out any major event of Mutahhari’s life, it is concerned with three subjects of his works and academic activities: namely, Iranian nationality, the Islamic veil and the Islamic Revolution. Although Haar refers to a considerable number of Persian publications about Mutahhari, he does not use Vathiqi Rad’s collection, which is regarded as the main source about Mutahhari’s life in Persian literature.16 Hamid Dabashi’s scholarly study on Mutahhari (1993) is part of his research on the ideological foundation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Although he discusses almost all political aspects of Mutahhari’s Islamic ideology, his book does not include much in the way of discussion of the economic dimension of this ideology, failing to mention two of Mutahhari’s major economics books.17 Vanessa Martin’s interesting analysis of Mutahhari’s political philosophy (2000) constitutes a part of her book on Ayatullah Khomeini’s ideology of the Islamic state, although it does not include Mutahhari’s social work and political activities.18

The Yad-namih-yi Ustad-i Shahid Murtaza Mutahhari, edited by ‘Abdul-Karim Surush in 1360/1981, is in fact the first publication in Persian about Mutahhari. It includes statements by various personalities from all over the world after his assassination. Apart from two articles written by Montazeri and Va‘iz-zadih about Mutahhari’s life, the rest includes different theological and philosophical articles presented by Mutahhari’s friends, in his memory.19 M. H. Vathiqi Rad’s two-volume Mutahhari: Mutahhar-i Andishih-ha (1364/1985) is regarded as a major source for Mutahhari’s life. It is mainly a collection of statements, interviews and articles issued and published by Mutahhari’s teachers and friends after his death, but it also includes a considerable number of valuable documents about him. Although it deals to some extent with the socio-political background of some of Mutahhari’s works, it does not assess them, in particular his philosophical analysis.20 These two volumes were republished in 1379/2000 under the title of Muslih-i Bidar with a different structure. The Jilvih-ha-yi Mu‘allimi-yi Ustad (1364/1985) is another collection of interviews and statements made by Mutahhari’s friends and students about his life and works, and includes a number of articles about his social philosophy.21 The Sairi dar Zindigani-yi Ustad Mutahhari (1370/1991) begins with an article written by Hujjat al-Islam Hashemi Rafsanjani about the role of Mutahhari in Iran’s Islamic movement, and continues with a relatively comprehensive analysis of Mutahhari’s personality, his way of thinking, his academic works and his political activities.22 It is particularly useful for some unpublished letters by Mutahhari about the Husainiyih-i Irshad and Dr Ali Shariati. The two volume Sarguzasht-ha-yi Vizhih az Zindigi-yi Ustad-i Shahid Murtaza Mutahhari (1375/1996) is another collection of interviews with the friends and students of Mutahhari,23 which is full of information concerning his life and political activities. They provide some background information to Mutahhari’s works and activities in Qum and outside the clerical establishment, and end with a number of documents about him, including Ayatullah Khomeini’s letters to him before the Islamic Revolution. However, they do not deal with Mutahhari’s own works and views. Ali Ba qi Nasr-abadi’s scholarly book, Sairi dar Andishih-ha-yi Ijtima‘i-yi Shahid Ayatullah Mutahhari (1377/1998) has provided a relatively comprehensive study of Mutahhari’s social and historical philosophy, but it does not deal with his political philosophy and Islamic ideology. Ustad-i Shahid bi Rivayat-I Asnad (1378/1999) provides a unique collection of SAVAK’s reports on Mutahhari’s political views and activities. The seven-volume Yad-dasht-ha- yi Ustad Mutahhari (1378/1999–1382/2003) is also a very useful collection of Mutahhari’s notes, comments and unpublished manuscripts.

This study aims to introduce Mutahhari to Western readers. To draw a clearer picture of his unique role as a major theoretician of the Islamist movements and a main architect of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the study takes a comprehensive form and covers almost all major aspects of Mutahhari’s works, political activities and social-political philosophy.

To enable the reader to gain a better understanding of Mutahhari’s life, a biography of him, in chronological order, is provided in Chapter 1. This covers the period between his childhood and his move to Tehran to work in 1951. Throughout this chapter, the major sociological elements surrounding Mutahhari and influencing his life, feelings and personality, including his family, friends, education, religious seminaries, his charismatic teachers and mentors, as well as some relevant political events and movements, are discussed. To provide a better image of his times, the discussion goes behind the political events, sketching a wider panorama for the reader.

The second chapter focuses on Mutahhari’s academic works and political activities. This part is indeed a sort of sociology of the intellectual, explaining the mutual exchange between Mutahhari and his times, demonstrating the reflection of the communal political needs on his works, and also the influences he left on his society. It covers the period from the beginning of his employment at Tehran University to his assassination in 1979. While clarifying Mutahhari’s influence on Muslim activists and the Islamic movements, the chapter draws an overall picture of the formation of these militant groups and religious associations. The well-known Islamic Associations of Teachers, Engineers and Physicians, the Islamic Coalition Groups (Haiat-ha- yi Mu’talifih-yi Islami), the Institute of Husainiyih-i Irshad, the Society of the Militant Clergy (the Jami‘ih-yi Ruh. aniyat-i Mubariz), the Qum Seminary (the Hauzih-i ‘Ilmiyih-i Qum), as well as the Muslim leftist guerrillas (Mujahidin-i Khalq and Furqan) are discussed in this section. The chapter also covers discussions of non-religious groups including Marxist activists and guerrillas. Moreover, it deals with Mutahhari’s philosophical works on a variety of issues relating to man, religion, society and history.

The focus of Chapter 3 is on Mutahhari’s analysis of the Islamic economic system, in contrast with the two main economic theories of capitalism and socialism. Mutahhari’s two major economic writings, Mas’alih-yi Riba and Nazari bi Nizam-i Iqtisadi-yi Islam are examined carefully. To present a theoretical foundation for an ideal Islamic banking system, Mutahhari’s attention is directed, in the first book, to the analysis of the baselessness and unlawfulness of usury; whereas the second book provides his socialist view on ‘machine’ as the main characteristic of modern capitalism. While trying to stand between capitalism and socialism, Mutahhari’s analysis tends, eventually, towards a preference for a state economic system. However, this chapter benefits, from time to time, from Sadr’s Iqtisaduna and his economic analysis.

Chapter 4 covers Mutahhari’s political perspectives from his earlier writings and later interviews and lectures, around the time of the Islamic Revolution. It puts his ideas within the framework of previous interpretations of the theory of Islamic rule (Vilayat-i Faqih), beginning with Muhaqqiq Karaki (d. 1533), and focusing on particular issues relating to questions of authority, sovereignty and legitimacy – such as the necessity of having a ruler or the nature of the state, the ideal type of relationship between ruled and ruler, what kind of Islamic rule: rule only by enforcement of Islamic law (Shari‘at) or rule also by a just and well-qualified jurist (vali-yi faqih). This part also reflects Mutahhari’s views on the role of the clergy in politics, secularism (Islam minha-yi Ruh aniyat), his analysis of the consistency between Islam and republicanism, and the need to protect the Islamic Republic from secularists and imperialists.

The transliteration system will mainly follow that used in the Journal of Islamic Studies (published by Oxford University Press) with the diacritical marks. However, where proper names have an established spelling in English language texts, that has been preferred to the transliterated version.

Notes

- Bazargan, Mahdi, in Mutahhari’s memorial speech, Abul-Fazl Mosque, Tehran, 5.2.1359/1980.

- Nomani, Farhad and Rahnema, Ali, The Secular Miracle, London and New Jersey, 1990, p. 38.

- Fischer, Michael and Abedi, Mehdi, Debating Muslims, Madison, 1990, p. 181.

- Algar, Hamid, ‘Introduction’ (to Mutahhari’s life) in: Murtaza Mutahhari, Fundamentals of Islamic Thought, trans. R. Campbell, Berkeley, 1985, p. 9.

- Dabashi, Hamid, Theology of Discontent, New York and London, 1993, p. 148.

- Martin, Vanessa, Creating an Islamic State, London and New York, 2000, p. 75.

- See the statement of Ayatullah Khomeini on 12.2.1358/1.5.1979, in: n.a., Sahifih-yi Nur, Vol. 4, Tehran, Bahman 1361/1983, p. 104.

- Surush, ‘Abdul-Karim, ‘Mutahhari: Ihya-kunandihi dar ‘Asr-i Jadid’, in: ‘Abdul-Karim Surush, Tafarruj-i Sun‘a, Tehran, 1366 (1987–8), p. 366.

- See an interview with Ayatullah Sayyid Ali Khamenei on 12.2.1360 (1981) in: M. H. Vathiqi Rad, Mutahhari: Mutahhar-i Andishih-ha, Vol. 1, Qum, Urdibihisht 1364 (1985), p. 222.

- Vathiqi Rad, Mutahhari, Vol. 1, p. 143.

- See interviews with Hujjat al-Islam Hashemi Rafsanjani on 12.2.1360 (1.5.1981) and 11.2.1361 (30.4.1982), in: Vathiqi Rad, Mutahhari, Vol. 1, pp. 127 and 131.

- Quoted from Vathiqi Rad, Mutahhari, Vol. 1, p. 415.

- Algar, Hamid, ‘Introduction’, pp. 9–22.

- Fischer and Abedi, Debating Muslims, pp. 181–211.

- Nomani and Rahnema, The Secular Miracle, pp. 38–51.

- Haar, J. G. J., ‘Murtaza Mutahhari (1919–1979): An Introduction to his Life and Thought’, Persica, 1990–2, Vol. XIV, pp. 1–20.

- Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, pp. 147–215.

- Martin, Creating an Islamic State, pp. 75–99.

- Montazeri, Husain-Ali, ‘Hakim-i Farzanih’ in: n.a., Yad-namih-yi Ustad-i Shahid Murtaza Mutahhari, Tehran, Shahrivar 1360 (1981), Vol. 1, pp. 171–3; Muhammad Va‘iz-zadih Khurasani, ‘Sairi dar Zindigi-i ‘Ilmi va Inqilabi-yi Ustad-i Shahid Murtaza Mutahhari’ in: n.a., Yad-namih-yi Ustad, pp. 319–80.

- Vathiqi Rad, Mutahhari: Mutahhar-i Andishih-ha (2 vols), Qum, Urdibihisht 1364 (1985).

- N.a., Jilvih-ha-yi Mu‘allimi-yi Ustad, Tehran, Spring 1364 (1985).

- N.a., Sairi dar Zindigani-yi Ustad Mutahhari, Tehran, Urdibihisht 1371 (1992).

- N.a., Sarguzasht-ha-yi Vizhih az Zindigi-yi Ustad-i Shahid Murtaza Mutahhari (2 vols), Tehran, summer 1370 (1991).

(© Mahmood T. Davari, 2005)

(Disclaimer: This material is made available here strictly for educational purposes)