Desirable and undesirable change in the Ummah - II

Developing Just LeadershipZafar Bangash

Safar 01, 1438 2016-11-01

Special Reports

by Zafar Bangash (Special Reports, Crescent International Vol. 45, No. 9, Safar, 1438)

This is the second part of Zafar Bangash’s article on “change”; the first part was published in the October 2016 issue of Crescent International, concluding with outlining some of the qualities of muttaqi leadership.

Long before Allah’s Prophet (pbuh) migrated to Madinah, he, through the three bay‘ahs, began to satisfy the needs of the two power blocs in Madinah, the Aws and Khazraj. When he got to Madinah, he even satisfied the needs of the Madinan Jews, entering into a constitutional arrangement with them and others in the Pact of Madinah. This was the first-ever written constitution outlining the rights and responsibilities of the state and its member constituencies. And from this groundwork emerges one of the greatest lessons of Islamic warfare: without the painstaking effort engendered in the Prophet’s (pbuh) leadership, Muslims may never have learned it. The stress footing of war separates those who give lip service to Allah (swt) and His Messenger (pbuh) from those who commit life-service to Him. This was proved over and over again through the Islamic military engagements in Badr, Uhud, Mu’tah, Khandaq, Yarmuk, Khaybar, and Hunayn.

Effective leadership motivates people to overcome obstacles to change. One way of achieving this is to energize them into satisfying basic human needs such as a sense of accomplishment, having a sense of control over their lives and the confidence to live up to Islamic ideals. Coping with change demands initiatives from groups of people at all levels of society. Initiative taking is a leadership activity. Multiple leadership activities could easily conflict and be at cross-purposes were it not for coordination through strong networks of informal relationships. Once again, consider the approach of Allah’s Prophet (pbuh). When he got to Madinah, he immediately established the Ansar and Muhajirun as brothers in every household. This inculcated the essential qualities of trust, accommodation, and adaptation helping to resolve conflicts that inevitably emerge in human relationships.

In Madinah, he built the first masjid outside of Makkah after the five daily salahs were institutionalized. Although salah is a required activity of Muslims, congregating and going to the masjid does not require any formal preparation. Muslim merchants were encouraged to setup their own marketplace governed by Allah’s (swt) rules of economic engagement. Muslims who had the wherewithal to purchase gifts for their children on special occasions were encouraged to buy similar gifts for their neighbors’ children should their parents not be able to afford such. Communities were required to know the poor and destitute in their environs and address the need before they were asked. All of this activity was taking place through informal networks as only the salah and the Pact of Madinah had been formally institutionalized. This helped to bind historically dispossessed elements in the society to the dominant power culture in the city.

Was such enfranchisement worthy of protection through the sacrifice of life for one who was traditionally on the margins? Certainly! Contrast this in today’s world with the speed of masjid-building activity in places where there is no Islamic state and the five-times salah taking place divorced of its vital imperative of anchoring Islamic leadership culture in the salah attendees. Building strong networks of informal relationships that coordinate leadership activities is an essential act of leadership.

During the time of Allah’s Messenger (pbuh), the fact of the matter is that most direction-setting activities and the development of informal networks took place before a single sword was lifted, a single arrow was fired, or a single spear was aimed. This is the kind of leadership that helps societies of ordinary people extraordinarily manage constant change.

In the contemporary age, we have witnessed similar achievements by Muslim strugglers. Whenever attacked by vastly larger and better-armed enemy forces, Muslims have frequently defied the odds by doing better than expected. Although they have been forced to react to external aggression, their resilience has frustrated the enemies’ plans. Further, while Muslims will not be able to match the weapons of their enemies in the near or even distant future, in most struggles, they have given a good account of themselves.

One cannot say the same about the mercenary armies of Muslim nation-states that do not fight on the basis of iman but for low-level loyalties such as nationalism. They have done more to integrate themselves into the social fabric of special interests dominated by corrupt opportunistic power blocs rather than establishing a meaningful social presence in their own populations, hence their dismal performance in almost every major battle. No military confrontation proceeds with a successful outcome as long as the people are unwilling to commit their lives for the cause. Allah’s (swt) promised help does not extend to Muslims fighting for nationalism, which is a form of shirk, or for personal glory or wealth. A glance at some contemporary conflicts imposed on Muslims will clarify this point.

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, most analysts predicted that the Afghans would have little chance against the world’s second most powerful military machine. The Soviet army had never been defeated and once it entered a country, it did not leave, they argued. A comparative analysis of the Soviet and Afghan weapons and manpower also clearly indicated that the Red Army would not only prevail against the Afghans but would also extend its reach beyond the borders into neighboring countries. The Afghans were viewed as ragtag bands of brave but foolish warriors that were no match for Soviet military might. Ten years later, when the Red army was driven out of Afghanistan, there was no Soviet Union left to return to. The ragtag Afghan bands had prevailed, contrary to experts’ analyses, not because of their superior weapons but on the strength of their iman.

While the Soviet army was busy slaughtering the Afghans, the Ba‘thists of Iraq were instigated by the imperialists and neighboring Arabian states to invade Islamic Iran, then in the throes of an Islamic revolution. They thought the revolutionary government would quickly collapse and the old order restored through the “safe hands” of such figures as Abolhassan Bani Sadr and Sadeq Qutbzadeh. Both had managed to penetrate the inner circle of Imam Khomeini and become president and foreign minister respectively in the revolutionary government. A few weeks into the Ba‘thist imposed war, Bani Sadr as president and, therefore, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, went to the Imam and advised him that in the absence of foreign backing and military support Iran was in no position to continue fighting and that it should accept the UN proposed ceasefire. The Imam dismissed such defeatist talk; instead he mobilized Iran’s revolutionary youth to confront the grand conspiracy of the international warmongers financed by the Arabian regimes. Soon thereafter, Bani Sadr fled and Qutbzadeh was arrested, tried, and executed for attempting to overthrow the Islamic government through a coup that included the diabolical plot to assassinate the Imam.

Islamic Iran single-handedly stood against the combined might of international kufr and for eight years valiantly defended the revolution. When the war ended in August 1988, Iran had achieved two of its three objectives: successful defense of the revolution and liberation of every inch of its territory. The only objective it did not achieve was to put Saddam Hussein on trial as a war criminal. The Americans themselves arranged the execution of Saddam 18 years later, partly because he had failed in the task assigned to him: destruction of the Islamic Revolution. He was not only provided arms and intelligence data but also given chemical and biological weapons that he freely used against Iran’s forces for eight years, sending thousands of young Iranian men to painful death.

Ultimately, the Americans turned against Saddam. But it was Islamic Iran that frustrated their plans by refusing to react in the manner expected by its enemies. Imam Khomeini inspired millions of young and old Iranians to defend the revolution, thereby writing a glorious chapter in the history of Islam. Could the Imam have been nearly as effective without developing a strong directional course (Walayat Faqih)? Could he have been as effective without bypassing the imperial state communication channels through energizing informal associations of students in the Hawzah networks? Could he have been as successful without first spending nearly 20 years infusing key elements of the Iranian society with the Islamic leadership culture, thereby enabling them to take control of their future destiny?

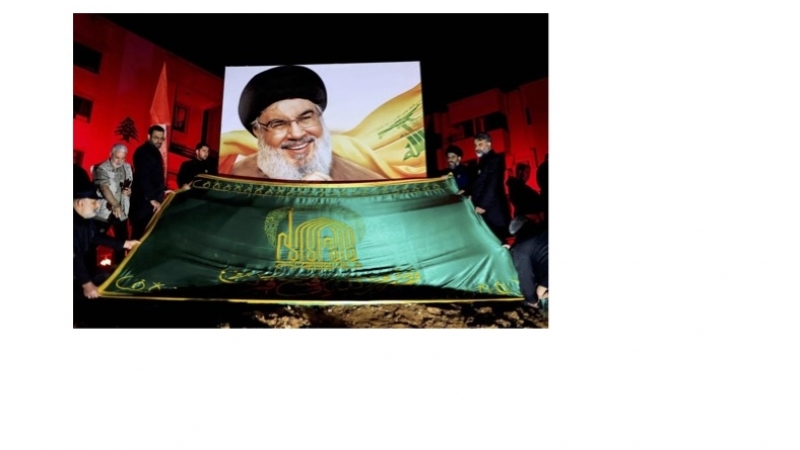

Hizbullah in Lebanon and Hamas and Islamic Jihad in Palestine have similarly demonstrated great resilience and thus achieved notable successes against enormous odds. Hizbullah’s story is especially remarkable given the fact that it consists of the most oppressed and downtrodden people of Lebanon. These are not the typical characteristics of a people who would be expected to stand up to Israeli military might, the most powerful military machine in the Muslim East. Hizbullah operated in an environment where both the Lebanese government and the Israeli-allied Phalangist Christian militia were hostile to it and at every turn tried to undermine its resistance. Further, Hizbullah operated against the backdrop of repeated Arabian army failures to throttle the Zionist military machine. Hizbullah did not possess sophisticated weapons like aircraft, missiles, or long-range artillery to confront the Zionists’ American supplied arsenal; its fighters only had AK-47 rifles and Kytusha rockets. Despite its lack of weapons, Hizbullah demonstrated that it was and is possible to defeat the Zionist invaders. From its birth in October 1983 to May 2000 when it drove the Zionist occupation army out of much of Lebanon (except the Shebaa Farms), Hizbullah showed how lightly-armed fighters can defeat a regular army possessing vastly superior weapons. It achieved a similar success in the 34-day war in July–August 2006 frustrating the Zionists’ plans to destroy it and install a puppet government in Beirut.

What is the secret of Hizbullah’s success? Hizbullah leader Sayyid Hasan Nasrullah himself has explained the movement’s strategy: to avoid, as much as possible, the Zionists’ strong points — air force, long-range missiles, and artillery — and use its own strength against their weak points. This was best demonstrated in the summer of 2006. Hizbullah had no anti-aircraft or surface-to-air missiles to shoot down Israeli planes. Thus, its only recourse was to seek shelter in underground bunkers from Israeli aerial bombardment. Hizbullah had built a vast network of underground bunkers in southern Lebanon in utmost secrecy. For nearly 20 years, Hizbullah has tightly integrated itself into its constituency by providing vital social services such as health care, schooling, distribution of aid, etc. It is well-known the world over that for any foreign aid to reach the people who need it in Lebanon and occupied Palestine, it must go through Hizbullah or Hamas. Formal institutional networks have been subverted by the enemies of Allah (swt), of the people, and of justice; thus in this type of environment Hizbullah has deftly constructed strong networks of informal relationships that are precisely and unselfishly managed by the leadership. Hizbullah provides vital services for its people and the people in return are willing to provide timely sacrifices to protect the security and stability they have gained. This is another one of Hizbullah’s strengths leading to its success.

During the time of its founder, Hasan al-Banna, al-Ikhwan al-Muslimun (Muslim Brotherhood) also achieved the same kind of success in Egypt because its social service activities integrated the Ikhwan tightly into the fabric of its important social and ultimately political constituencies. In the face of the receding colonialism, it provided an integrated vision of a vibrant Islamic society, putting into motion Islamic welfare, representation, and foreign aid models. True to form, just like today, these activities squarely confronted entrenched ruling and special interests. In the 2012 elections, the Ikhwan-backed party was able to secure a clear majority of seats in parliament as well as the presidency only to be subverted a year later by the military through a brutal coup.

Hizbullah’s example, like that of Islamic Iran’s and the Afghan mujahidin, points to what needs to be done when confronted by external aggression. Every aggressor attempts to impose change on the victim society to achieve his nefarious designs. It is important for victims not to react in a manner that would facilitate the aggressors’ intended purpose. A successful defense must include taking the initiative away from the enemy by frustrating his plans and not reacting in a predictable manner. By changing the rules of the game, such as waging asymmetrical warfare, smaller, even lightly armed fighters can frustrate the enemy’s plans and inflict defeat.

In the foreseeable future, Muslims will not be able to acquire the kinds of sophisticated weapons their enemies possess. Their only recourse is to establish their own rules of engagement. When confronted by external aggression, people often improvise. Self-preservation and self-defense are not crimes under any law, no matter how much the West may denounce these as terrorism. It is the imperialist regimes, not the struggling Muslims that indulge in crimes against humanity. What is important to keep in mind is not to play by the enemy’s rules. The tide in global politics is slowly but surely turning in favor of Muslims despite the unleashing of extreme brutality against them. There is still a long struggle ahead but at last we can see some light at the end of the long, dark tunnel.

Pull quotes:

Whenever attacked by vastly larger and better-armed enemy forces, Muslims have frequently defied the odds by doing better than expected. Although they have been forced to react to external aggression, their resilience has frustrated the enemies’ plans. Further, while Muslims will not be able to match the weapons of their enemies in the near or even distant future, in most struggles, they have given a good account of themselves.

In the foreseeable future, Muslims will not be able to acquire the kinds of sophisticated weapons their enemies possess. Their only recourse is to establish their own rules of engagement. When confronted by external aggression, people often improvise. Self-preservation and self-defense are not crimes under any law, no matter how much the West may denounce these as terrorism. It is the imperialist regimes, not the struggling Muslims that indulge in crimes against humanity. What is important to keep in mind is not to play by the enemy’s rules.