Egypt’s Terminal Decline

Anwar al-Sadat lost the war his own general was winning

Developing Just LeadershipAyman Ahmed

Muharram 21, 1440 2018-10-01

News & Analysis

by Ayman Ahmed (News & Analysis, Crescent International Vol. 47, No. 8, Muharram, 1440)

This month marks the 45th anniversary of the Egyptian-Syrian war with Zionist Israel. In a surprise attack in October 1973 — the Zionists knew about it through the treacherous King Husayn of Jordan but did not take it seriously — Egyptian and Syrian armies launched operations on two fronts.

Syrian tanks rolled across the Golan Heights quickly overpowering Israeli colonial forces and then headed straight down toward the Sea of Galilee. Lightly armed Egyptian troops, on the other hand, crossed the Suez Canal in boats armed with high-powered water pumps and hoses. Israeli troops were sitting on the other side of the Canal confident in the belief that if attacked, Egyptian armor would get stuck in the huge sand embankments the Israelis had created. This was referred to as the “Bar-Lev line” named after the Israeli general who conceived of this type of defence.

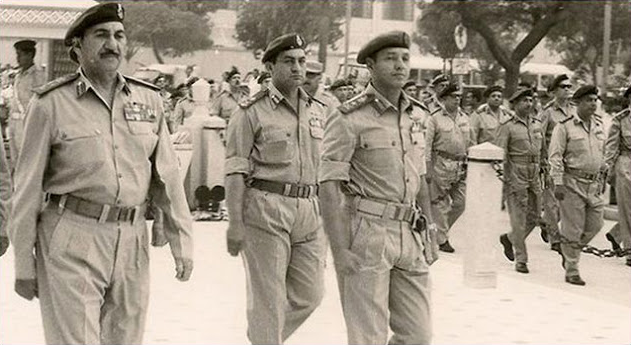

Theoretically, the Zionists were right but a charismatic Egyptian general, Muhammad al-Shadhili, thought out of the box. Instead of using conventional means, he conceived a novel plan to breach the Bar-Lev line. He used high-powered water hoses to punch huge holes in the sand dunes through which Egyptian tanks could easily roll into the Sinai. General al-Shadhili and his men had practiced this for months and honed their skills into an art.

It was the month of Ramadan and most Egyptian soldiers were fasting as was General al-Shadhili. Given their zeal, they quickly overpowered Israeli defences and headed into the Sinai Peninsula under the command of the dynamic general. In their arrogance, the Zionists had not stationed any troops in the Sinai in the mistaken belief that after Egypt’s defeat in the June 1967 war, it would not dare to launch an attack on Israel.

After the June 1967 war and decimation of the Egyptian army, the Zionists launched a war of attrition against Egypt targeting its industrial sites. It was routine for Israeli planes to bomb Egypt and the latter was unable to defend itself.

The fiery but ultimately incompetent Jamal ‘Abd al-Nasir had died of a massive heart attack in September 1970. His successors fought for control, with Anwar al-Sadat ultimately emerging on top. Sadat was a clown compared to ‘Abd al-Nasir. Every year he issued threats against Israel that never materialized. It was Sadat’s clownish antics coupled with Egypt’s 1967 defeat that led to complacency in Israel. Thus, prior to launching the war in October 1973, Sadat had issued another of his customary threats to Israel to vacate the Sinai Peninsula or else. The Zionists as usual greeted this latest threat with howls of laughter.

Once the Egyptian troops had crossed the Suez Canal and obliterated whatever Israeli defences there were, there was nothing stopping them until the Giddi and Mitla Passes halfway between the Suez Canal and the Israeli border. General al-Shadhili wanted to drop Egyptian paratroopers behind the Israeli forces guarding the passes. Had permission been granted, these Israeli troops would have been trapped and would have had no choice but to surrender.

It was at this point that then Israeli Defence Minister, the one-eyed General Moshe Dayan contemplated committing suicide. Israel had badly miscalculated and was caught napping. Unfortunately Sadat got cold feet and refused General al-Shadhili’s repeated requests to drop paratroopers behind Israeli lines in the Sinai. Had such permission been granted, it is possible the Muslim East landscape would be very different today.

It was Sadat’s cowardly behavior that turned Egypt’s victory into defeat. General al-Shadhili was removed from the Sinai campaign and other generals that took over were quickly neutralized by the Israeli army leading to the encirclement of Egypt’s Third Army in the Sinai. Ariel Sharon who a decade later would earn the epithet, the Butcher of Beirut for his role in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps’ massacres in September 1982, was able to cross the Suez Canal and encamp on the other side.

Indecision or lack of courage at critical moments in war makes the difference between victory and defeat. General al-Shadhili was winning the war; Sadat lost it. The story of the October 1973 war — aka the Ramadan War or even the Yom Kippur War because the Jews were commemorating Yom Kippur — would be incomplete without another important detail. Henry Kissinger — yes that evil man who has one leg in his grave — was US Secretary of State at the time. He not only rushed US weapons to Israel (it was called the “air bridge”) but also told Sadat to halt his campaign and the US would get him the Sinai Peninsula.

Ever the bootlicker, Sadat accepted Kissinger’s offer and even allowed Israel to trap his army. With battles on the Egyptian front stalled, the Zionists turned their attention to the Syrian front and were able to push the Syrian army out driving it back beyond the Golan Heights where it still stands.

Following ceasefire and backdoor negotiations between Israel and Egypt under US oversight, Sadat surprised his people and the world when he showed up in Jerusalem in November 1977 to address the Israeli Knesset (parliament). “Peace” talks soon followed resulting in the Camp David Accords of 1978 under the watchful eye of President Jimmy Carter. Israel vacated the Sinai Peninsula on the condition that Egypt would not deploy any troops there. Imagine a ruler accepting such a humiliating condition on his own territory!

For this treachery, Sadat was given the Nobel Peace Prize together with the arch terrorist Menachem Begin who was the prime minister of Israel and signed the Camp David Accords on behalf of his country. Egypt established diplomatic relations with Israel that many Egyptians viewed as betrayal and humiliation. The Palestinian cause was abandoned and has suffered grievous harm as a consequence.

Relations between Sadat and the rulers of Israel warmed up so much that Jihan al-Sadat, Anwar al-Sadat’s wife, was seen dancing with Israeli rulers, among them Ezer Weizman. Many Egyptians felt deeply humiliated. It was as a result of this humiliation brought on by Sadat’s treachery that a group of young Egyptian military officers led by Lieutenant Khalid Islambuli attacked the military parade and shot and killed Anwar al-Sadat on October 6, 1981. It was the anniversary of the October 1973 war and Sadat and his generals were watching a military parade.

Khalid Islambuli’s courageous act put an end to one traitor but others have stepped in his shoes. Husni Mubarak, the air force chief at the time, survived the attack and succeeded Sadat as president. He ruled with an iron fist until he was ousted in a people’s uprising in February 2011.

By then, Egyptian generals had become accustomed to the easy life and instead of practicing for war, they were more interested in acquiring real estate and buying business ventures. Today, the top echelon of the Egyptian army is staffed by business tycoons who are comfortable with Western industrial barons chomping cigars and drinking wine than practicing in battle fatigues.

Egypt’s current pharaoh, the baby-faced general, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has surpassed even his predecessors in cruelty and bloodletting. He felt no remorse in killing thousands of innocent people in cold blood following his coup in July 2013. He has the dubious distinction of overthrowing the first legitimately elected government in Egypt’s entire history.

Only last month (September 8), the Cairo Criminal Court sentenced 75 people to death, all of them members of al-Ikhwan al-Muslimun. Their “crime” was that they had participated in peaceful protests in July–August 2013 against the ouster of a democratically elected government by the brutes in uniform.

Egypt under el-Sisi is now a Zionist colony.