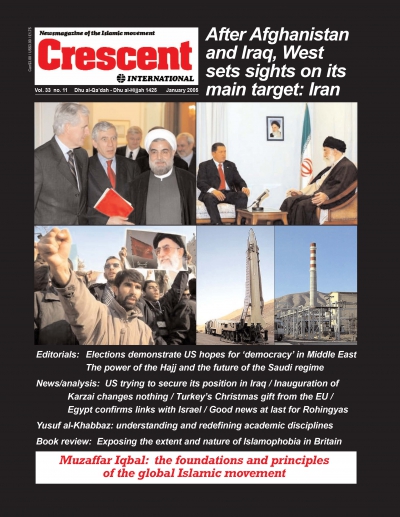

Crescent International Vol. 33, No. 11

Newsmagazine of the Islamic movement

Iqbal Siddiqui

Dhu al-Qa'dah, 1425 2005-01

An Islamic state is an ideological state; it is not a nationalist state and it is not a sectarian state. Achieving this, however, is easier said than done. An Islamic state rooted in an ideological Qur’an and a strategic Sunnah proved difficult to sustain for the early generations of Muslims after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, upon whom be peace. It is now proving just as hard to reconstruct after the death of Imam Khomeini (r).

Dual Citizenship: British, Islamic or Both? Obligation, Recognition, Respect and Belonging by Saied R. Ameli and Arzu Merali. Pub: The Islamic Human Rights Commission, London, November 2004. Pp: 84. £7.00. Social Discrimination: Across the Muslim Divide by Saied R. Ameli, Manzur Elahi and Arzu Merali. Pub: The Islamic Human Rights Commission, London, December 2004. Pp: 78. £7.00. By Laila Juma

Shortly after US troops occupied Baghdad in 2003, president George W. Bush warned Iraqis that there was no prospect of political institution-building or transfer of power to an Iraqi government so long as military resistance continued. At the time, the warning was taken as a pretext for the US to maintain political control for as long as possible; eighteen months later, the process of a transfer of power to an elected Iraqi government is well advanced, despite the fact that resistance remains a major problem in many parts of the country. The change in the US’s position is partly a measure of its failure in Iraq, in that it has repeatedly had to adjust its plans because of the strength of Iraqi resistance.

One of the key justifications that the US has used for its aggressive foreign policy in the Middle East has been that it is working to promote democracy and political freedom for the oppressed peoples of the region. Its supporters are claiming major victories in this department at the moment, as the pro-American Hamid Karzai supposedly became Afghanistan’s first democratically elected president last month, and elections for a democratic Iraqi government are due to take place at the end of January. The reality, of course, is very different, as all but the most west-toxified observers recognize.

As this issue of Crescent International goes to press, some 2 million Muslims from all over the world are converging on the Haramain to perform the Hajj, the assembly of the united Ummah that is also the greatest act of personal ibadah that any Muslim can perform. The Muslims that come to perform the Hajj come from every part of the world and from all sectors of the Ummah, to stand together in the same simple clothes, resembling the shroud in which we will one day be buried, standing equal before the Creator regardless of their wealth, power and social standing, and praying for forgiveness for their past deeds and errors. At least, that is how the Hajj is supposed to be.

The academic disciplines through which most people study and understand modern life are almost entirely based on Western historical experiences and the needs opf western societies. They thus remain replete with cultural and political implications that few understand. YUSUF AL-KHABBAZ discusses efforts to criticaly redefine these disciplines.

The election campaign season began officially in Iraq last month. Like much else in the political life of modern Iraq, these elections, scheduled for January 30, have led to fierce competition. Nowhere can the intensity of electoral clamoring better be seen than in the number of electoral tickets competing for seats in the 275-member National Assembly.

The two car-bombs that rocked the Shi’a holy cities of Karbala and Najaf on December 20, killing at least 62 people and wounding 120, have focused attention once again on the deepening sectarian passions in Iraq that have opened the door to speculations about a looming civil war and the possible “Lebanonization” of Iraq.

Given the size of its territory and population and the educational standards of its people, Egypt could be a power to reckon with and could, if it chose, play an effective and beneficial role in African, Arab and Muslim affairs. Instead, its government has chosen to serve the US’s interests, including the survival of Israel, the drastic limitation of Palestinian ambitions and the suppression of Islamic revivalism.

To gauge the true depth of moral and intellectual decline of the ruling elites in the Ummah, one has only to see their reactions to the plight of the Muslims in Iraq and Palestine under their occupiers. With the exception of the Rahbar of Islamic Iran, Imam Seyyed Ali Khamenei, not one Muslim ruler has uttered a word against the brutalities being inflicted on these hapless peoples, much less done anything to help them.

After weeks of promises and reversals, the Malaysian government, which practises an official policy of zero-tolerance towards refugees and foreigners without valid documents, has formally announced its decision to recognise the thousands of Rohingya Muslims in the country as political refugees.

So powerful is the West’s propaganda that mere mention of the word “warlord” immediately conjures up images of a bearded thug terrorizing hapless civilians in Afghanistan. Just as terrorism has been made synonymous with Muslim activism, so warlordism has become the exclusive preserve of the Afghans.

Hamid Karzai was sworn in as president of Afghanistan on December 7 amid unprecedented security: foreign troops protected him from the very people who are supposed to have elected him to his office. In attendance were not only US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld but also vice president Dick Cheney, with an entire hospital in tow, just in case his pacemaker should stop during the ceremony.

The deal recently negotiated by Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the Turkish prime minister, in Brussels on his country’s longstanding quest for membership of the European Union is, by general agreement, unfair and humiliating, and by no means indicates – let alone guaranteeing – that Turkey will eventually be allowed to become a member of the EU.